A rose is a rose is a rose

In Müller's poetry collection Winterreise, the reader is taken on an imaginative journey through the darkest corners of nature and the soul after the protagonist is betrayed by his beloved. In Gute Nacht, he repats almost obsessesively that “she spoke of love, her mother of marriage,” and the betrayal of this unfulfilled dream is almost too much for him to bear.

What characterizes a fantasy is self-centeredness and the lack of a victim. You won’t enjoy an imaginary adventure if you relativise or question your own experience.

How would the song cycle have sounded if she, the object of love, had been given a voice?

Who was she, the deceitful woman?

According to French-Israeli sociologist Eva Illouz, the way of maintaining male status in society has changed since the Romantic era. Being “a real man” in the 19th century meant being able to feel and express strong emotions, as well as making and keeping the promise of that those emotions would be eternal.

The female ideal during this period, on the other hand, was more reserved and restrained in emotional communication.

This also had to do with the fact that a woman considered unstable and "hysterical" would end up in an asylum and undergo a hysterectomy, but we’ll ignore that for now!

While women were more or less without rights in society at large, they seem to have had a position of power in the courting process—at least on an emotional level.

In today's much more equal society, Illouz argues that women have taken over the relational role of those with strong feelings, making declarations of love and wanting to commit. Think, for example, of the scene in Ruben Östlund's “The Square” where the protagonist refuses to give his used condom to his one-night stand out of fear that she might impregnate herself in the bathroom.

The man, on the other hand, has taken on the role of the reserved, silent, strong type, who does not express his feelings—but who is the emotional power-holder.

However, this male ideal brings with it much harm: mental illness and isolation. We all know this ideal unfortunately claims many victims.

Why must there be Romantics and Power-Holders, why must one of the genders always be "the silent one"?

The male experience of women's emotional power has been widely reported, for example in Winterreise. Therefore the "woman without a voice," the dancer, takes the stage in the first half of the concert. After the power shift, the "silent, strong" man gets a chance to speak (through dance).

What happened to his voice after the power shift?

Is power in the long term the ability to express one's emotions, or is it the ability to control them?

Are we fighting against each other or within ourselves?

The concert begins with a manifestation of a woman who is compliant, who adapts. The male dancer enter, and the dancers' duet demonstrates traditional gender roles. After this, there is a shift in power and in musical tonality, as we move from hearing music my Franz Schubert to past and present female composers for the second half of the concert.

Ida Henriette d'Fonseca was a Danish composer who wrote her own song cycle to Müller's poetry collection Winterreise. Her “Einsamkeit” is the music for the male dancer's solo, which deals with his role after the power shift.

The concert ends with Caroline Shaw's "And So," sung by a soprano. The soprano is the voice of the silent woman.

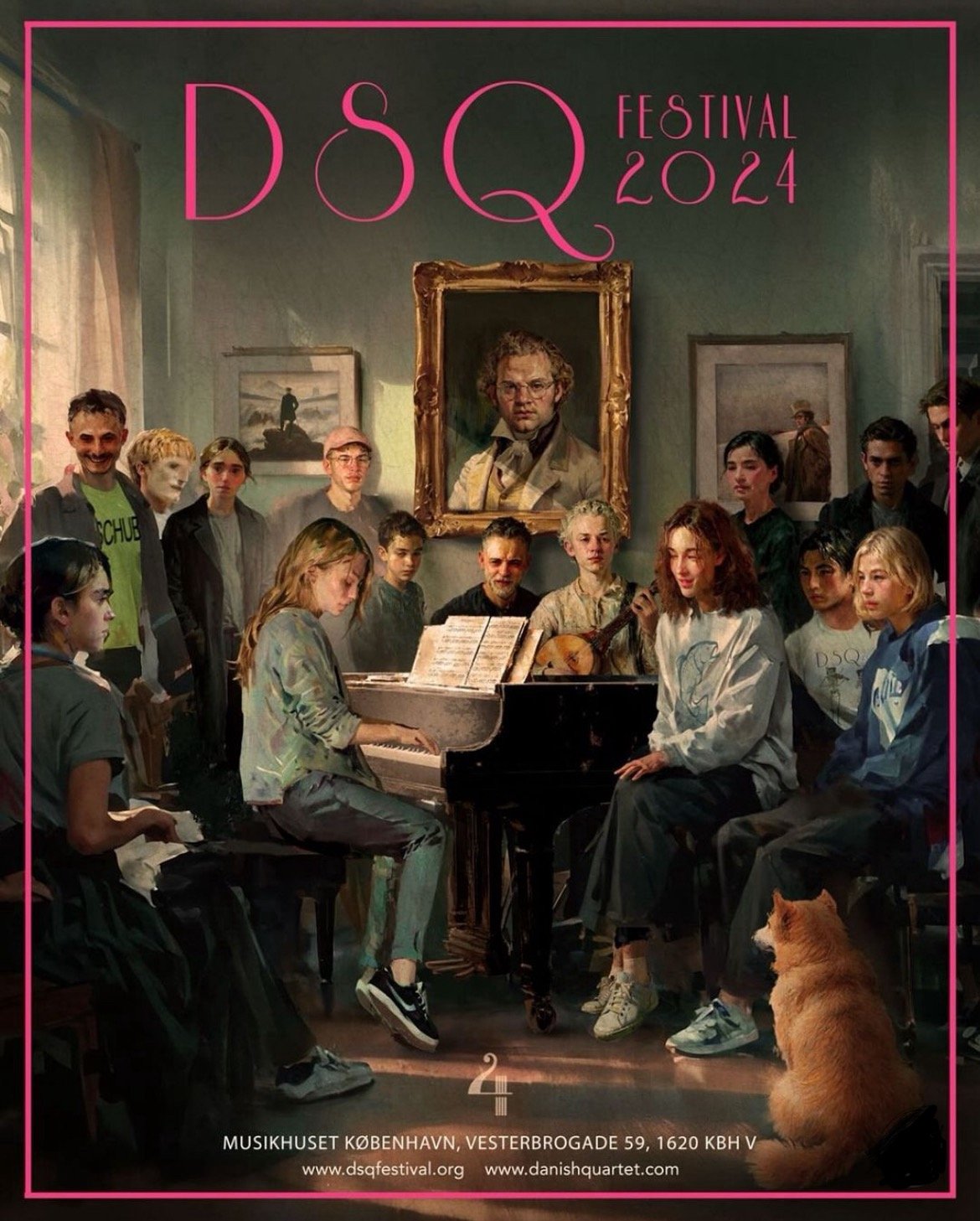

This program was commissioned by the Danish String Quartet

Choreographer and dancer: Lúa Mayenco

Dancer: Sebastian Mayorga Suhr

Singer: Christine Bach Tofft

The Danish String Quartet

Arrangements by Rune Tonsgaard Sørensen

Photographer: Caroline Bittencourt

Premiere October 31rst, 2024